Louis Hennepin and First Contact with the Dakota People

How a Franciscan priest ended up being the first European to make contact with the native peoples of the upper Midwest.

This is a bonus article for Meridians:

EP3: From The Lakota Sioux to Brendon Grimshaw: A Story of Conservation

To listen to the episode, search for "Meridians" wherever you get your podcasts.

Spotify | Apple | Podcast Addict | Pocket Casts

Latest Episode:

Who was Louis Hennepin? Where was he from? What did he do?

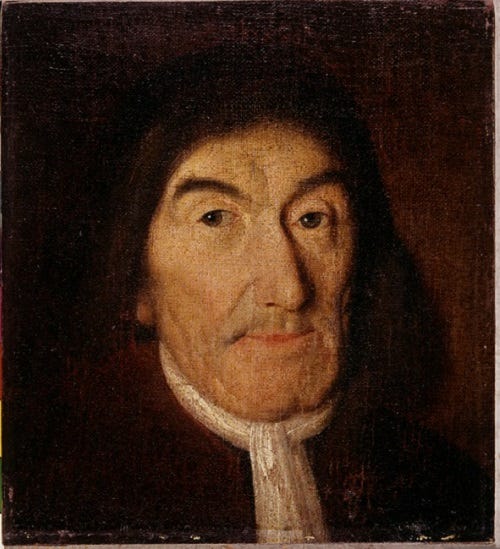

Antoine Hennepin was born in the Spanish Netherlands in 1626 (He wouldn’t be known as ‘Louis’ until later). The Spanish Netherlands was a collection of states in the Holy Roman Empire run by the Spanish branch of the Hapsburgs family, the Spanish Crown. While he was living in Béthune it was conquered by Louis the 14th of France.

With the influence of France suddenly dominating his area, Hennipen would then join the Récollet Order of Friars Minor (aka, Franciscan Order). They were established as a reform movement within the Franciscan order, seeking to observe the Rule of St. Francis more strictly. These guys took vows of poverty and devoted their lives to prayer, penance, and spiritual reflection. Hennepin would become a priest and missionary for this work and eventually be assigned to travel to New France (A large area of North America at the time).

How did Hennipen end up in what would later be Minnesota?

Hennepin had traveled around Europe as a young man and had a great interest in seeing the world. He would hear stories of missionaries traveling to exotic parts of the world and untamed wilderness.

In 1673, he was sent to Maastricht, Netherlands where he became a military chaplain. The next year he was sent to the Battle of Seneffe, a part of the Franco-Dutch War, where he ran into Daniel Greysolon Dulhut (Dulhut would go on to have Duluth, Minnesota named after him). After the battle, he was ordered to go to La Rochelle, France where he would soon set sail for the New World. He left for the New World in 1675.

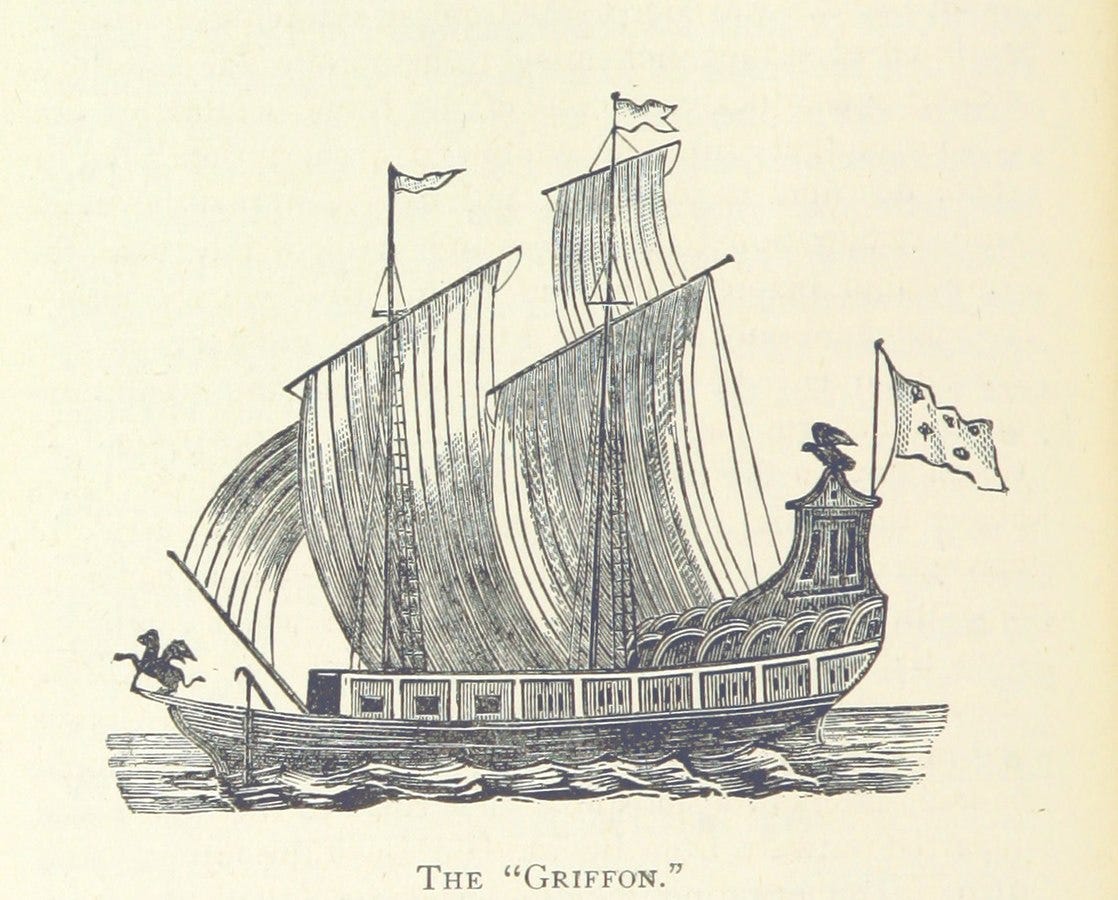

I couldn’t figure out what ship he traveled on but it likely would have been a merchant vessel. These boats were outfitted for colonial exploring and would be typical for around the time Hennepin would leave. One such vessel that would be similar to the one he would have traveled on is “Le Griffon”

Hennepin spent his first three years in the New World exploring what is now Quebec. While exploring the area, he would get a claim to fame for being the *first* non-Native American to document the Niagra Falls waterfalls.

Staying in line with his order, he lived very simply. On his travels, he would only bring a portable altar, a blanket, and a mat made of rushes (dried plants that were woven into mats) to sleep on.

In 1678, Hennepin would join up with Robert Cavelier de La Salle. La Salle was a French Explorer sent by the King of France to explore the Mississippi River. This group would depart near Niagra Falls and be the first non-Native Americans to navigate Lakes Erie, Huron, and Michigan.

They Landed in what is now Green Bay Wisconsin and then traveled by canoe and foot to what is now Peoria, Illinois. At this point, La Salle and many others felt they had run low on food supplies and apparently didn’t they they had the right supplies for navigation. I wish I could have figured out what exactly that means, the source wasn’t very clear. Only three men went on: Father Hennepin, Michel Accault, and Antoine Auguel Du Guay.

These three men made their way to the Mississippi River. Once the river thawed, they started making their way upriver, which would have been mid-April 1680.

Contact with the Locals!

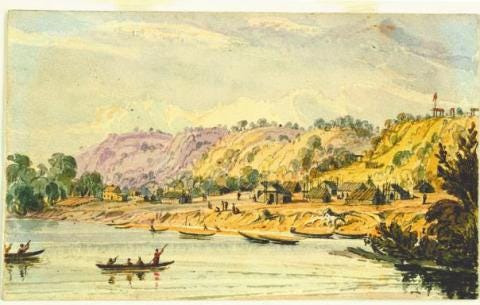

These 3 made their way up the Mississippi River to Lake Pepin. This is where things got pretty wild for them. They ran into 120 Dakota Native peoples and their several dozen canoes. Father Hennepin and the other two men were then taken to see the tribal elders in Kaposia. This turns out to be an important village along the Mississippi River near present-day St. Paul. The area was of great importance to the Dakota tribes, who would regularly visit and live in the village. There was a tradition of having burial mounds on the high bluffs in the area.

Arriving in Kaposia, it was then decided that the three white men would be taken to a village on the south shore of Mille Lacs, which was about 80 miles to the north. They would stay in this village for two months.

Hennepin and his men needed to travel down the Mississippi River to find a place to get more supplies. As they traveled south, they ran into a waterfall, which he would name “The Falls of St. Anthony.”

Hennepin and the men made their way to Prairie du Chien, a small trading post that had just been established on the Mississippi River the year prior. They were able to load up on supplies and head back upriver to return. So, they weren’t very *captive*, they could have just returned home from here but chose to return to the Dakota tribe willingly.

On their way back, they had a very bizarre encounter. Hennepin ran into an old acquaintance from the war in France, Daniel Greysolon Dulhut! Dulhut would help the three men make their way back to Mille Lacs. Then, over a month, Dulhut negotiated with the tribal Chief to allow the men to return home to Quebec.

So then, Father Hennepin and the other two men made their way back to Quebec. Hennepin would actually return all the way to France.

He wrote three books, one of which would slander La Salle, saying: “Sieur de La Salle wanted all the glory and secret knowledge of this discovery for himself alone. This is why he sacrificed several persons to prevent them from publishing what they had seen and from foiling his secret plans.”

Father Louis Hennepin gave great insight for Europeans into what life was like amongst the indigenous cultures of the upper Midwest. He learned a lot about their lifestyle and customs and even picked up some of their language. His name is remembered as being the name of the county that Minneapolis resides in as well as having several other locations, streets, etc, being named after him in the central Minnesota area. He would spend his final days in a Roman Monastery and pass away around 1705.